Rolling deep with the Earth

“If we can just get this ball rolling, this ball will roll on its own,” says Painting & Drawing Professor Kim Anno.

Faculty came together to start a new school at CCA—the E-school, an environmental justice collaboration across divisions that topples figureheads and centers frontline communities. “It’s a chance to have an environmental justice conversation with my colleagues across programs,” says Painting & Drawing Professor Kim Anno. “I couldn’t think of a better group to do it with and I’m so motivated!” The “E” in E-school stands for eco and other e-words associated with it—Earth, eco, echo, ecology, each other. Its aim is to collaborate with each other and the Earth itself.

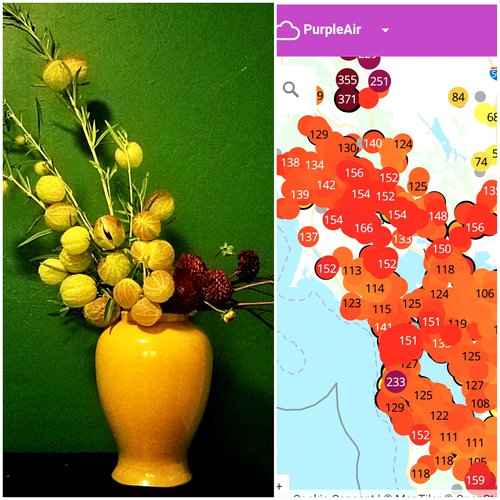

The collaboration began prior to the pandemic, and has been growing amid ferment. Here in the Bay Area, facing climate chaos head-on starts with the assertion that environmental justice means racial justice, social justice, and a collective sharing of power. The program launched this semester as gale-force winds blew across the Bay Area and sparks rained down inland, a branch hit a power line, and we learned Lightning Complex fires reignited near Santa Cruz, California. They’d smoldered for months underground.

Globally, the polar vortex moved south. The power grid in Texas had been down and many people there spent weeks without heat or water. “The toll of COVID-19 on essential workers, the confluence of climate refugees with the Bay Area’s housing crisis, and the impact of wildfire smoke on communities of color already burdened by environmental toxins have revealed a confluence of deep-seated legacies of racial and class inequity with the rapid and unceasing grind toward climate change,” E-school faculty say.

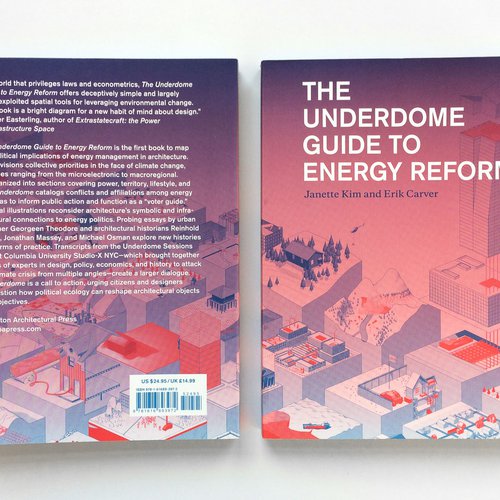

Environmental justice means sharing resources. Sharing guest speakers across four courses at various points during the semester are Architecture Assistant Professor Janette Kim, History of Art and Visual Culture Professor Ren Fiss, Jewelry and Metal Arts Co-chair and Associate Professor Curtis Arima, and Painting and Drawing Professor Kim Anno.

Anno’s student, International Interior Design Association Campus President Saieesha Adlakha, studies air pollution in Delhi, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

College is a conduit to materializing values that are emerging or ignored. The E-school at CCA makes these values visible and repeatable. Their mission: “Through art, design, and scholarship, we strive to make CCA a leader in the environmental justice movement.” Fiss says, “Faculty want to connect students to real-world projects.”

Anno’s student, International Interior Design Association Campus President Saieesha Adlakha, studies health disparities in Delhi, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

Environmental justice and climate justice are, Anno says, “a refocusing of the master lens—the dominant paradigm of environmentalism—with an understanding of how race and class are impacted by climate change. Climate justice takes seriously the pollution and carbon created by the developed world and how developing nations suffer disproportionately.”

Anno says, “We don’t start with the Sierra Club or John Muir.” Figureheads like these aren’t known for following the principles of environmental justice. “I ground environmental activism coming out of Indigenous and marginalized communities as an aim,” she says. “Other colleagues want to do it too.”

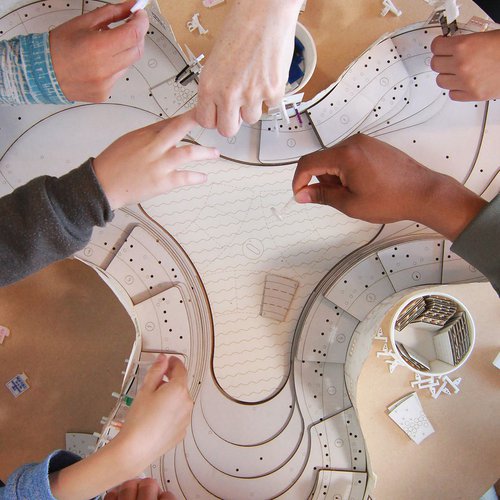

Kim’s architecture students offer alternatives by learning from groups like East Oakland Collective and by “framing environmental questions around maintenance, justice, and non-exclusive rights to resources like energy and water,” Anno says. “During the pandemic, we’ve had an opportunity to get people from all over the world to speak.”

“We’ve had a really vibrant lecture series,” says Fiss.

Fracking, soil degradation, and sea-level rise are heavy topics. How do faculty make them approachable and not overwhelming? Kim says, “I have my own gothic tendencies, so I actually kind of enjoy the tension embedded in these questions. But at the same time, I feel that the most palpable kinds of joy in this kind of work emerge when you realize that environmental resources can be shared, redistributed, and maintained in a way that is generous, plentiful, and delightful.” And Ohlone people all over the Bay Area are asserting their rights to steward reclaimed land.

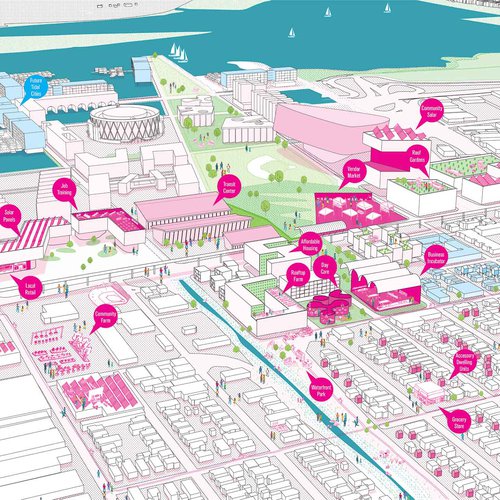

Cover of 2020 book, to be developed in spring 2021. Designing a Just City, 2021. 10 x 8 inches. © CCA Architecture Division. Student contributors, Ed. Janette Kim.

Art moves movements

“Art as provocation is very powerful,” says Anno. Works of art can move people to change, saving Earth in the process. Alternatives to five centuries of bad decisions include collective decision-making and cooperative-ownership.

E-school students wrestle with stratification. “CCA students aren’t homogenous,” says Anno, “but exist inside all the hierarchies of society. Their skills as artists and designers are the key to their efficacy on climate change. The artist’s role is unique in this regard.” Typical environmentalist stories “promote sustainability in a way that’s complicit with a culture of economic growth,” says Kim, “and that continues to be extractive and inequitable.” That’s a problem.

Kim’s Urban Imaginaries architecture course teaches that “the greatest challenges to social justice and environmental health aren’t just accidental—they’re the result of priorities and values that still linger today.” For example, she says, “environmentalist narratives have focused on natural preservation in a way that has actively expelled Indigenous people from land.” She created the course to reimagine cities, to look at “the way land has been parceled and commodified, and to explore systems of racial and class discrimination—from red-lining to gentrification.”

Youth are future elders

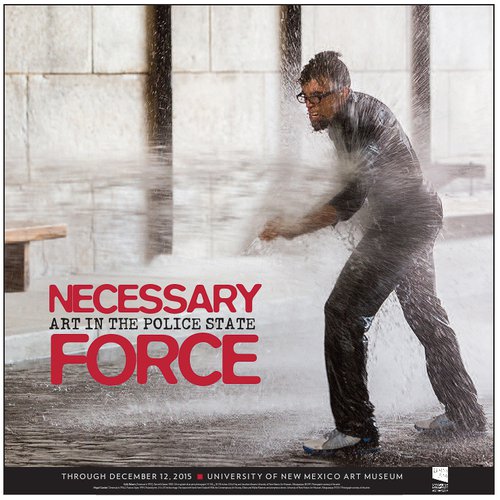

Fiss’s course, Environmental Art / Environmental Justice, has hosted speakers from Youth Versus Apocalypse and the Sunrise Movement, both youth-led. “Youth taking ownership,” says Fiss, “that’s a really key point and I think it’s the biggest challenge.” When Sunrise visited, “one speaker had just graduated from college, and one was a junior in high school. Another was taking time off from high school to work full time for the movement. I want students to see themselves reflected in the leadership and priorities of these organizations,” says Fiss. “It’s important that students find their own agency,” Fiss adds. “Effective activism is not easy—often an effort fails at first. Students can learn from that and understand it takes commitment.”

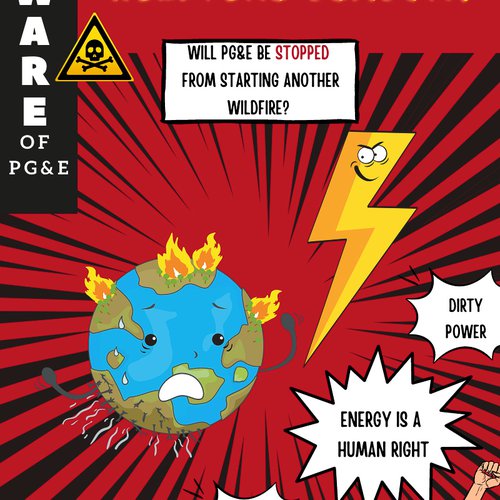

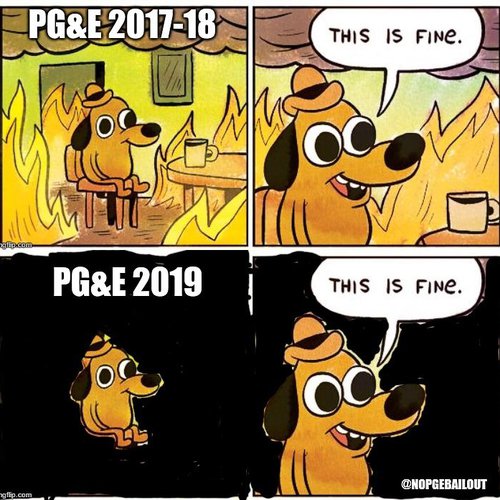

As an E-school teacher Fiss says, “it’s important to connect students to local issues and movements, while also learning about related issues and activism across the globe.” For example, Fiss’s class learned about community-based power and resilience efforts in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. At the same time they had a visit from Reclaim Our Power, a Bay Area utility justice campaign led by frontline communities. Reclaim Our Power has been fighting PG&E bailouts while PG&E avoided taking responsibility for its outdated equipment, sparking wildfires and shutting off power to people with disabilities. Students have the opportunity to get engaged and contribute to Reclaim Our Power’s visual campaigns. Fiss says a number of their students “feel a strong connection to these issues already, their families and homes impacted by California fires.”

“One of the biggest challenges,” says Fiss, “is how to address students who feel they’re helpless, hopeless, or don’t have time.” Collaboration opens a door for them to get involved. “They can experiment with putting their vision in the service of something bigger,” says Fiss. “They have amazing imagination and skills to bring to climate action.”

CCA radio podcast, Louella Evans, Earth Parks, Part 5: Point Reyes, California, 2021. Hosted by Anno’s student Louella Evans. Courtesy of CCA radio.

Green space over radio waves

Anno’s course is called Parks, Environment, and Leisure. It uses the lens of environmental justice to study the politics and aesthetics of parks. Students are storytelling via a CCA Radio podcast called Earth Parks, sharing audio from Shushan Park in China, to Lake Tahoe in California. Anno asks each student to, “whatever country you are in, find out about the history of a park, how it was established, the effects of climate change and sea-level rise on the area and its population. Who can adapt easier and faster? Who will be left behind?”

Climate change impacts us as people, but also impacts the flora and fauna within our parks. One episode talks about how conflicts are escalating in Point Reyes, California, between ranchers and those who work to protect wildlife and water. More than 5,000 dairy and beef cattle graze where 500 endangered Tule Elk live.

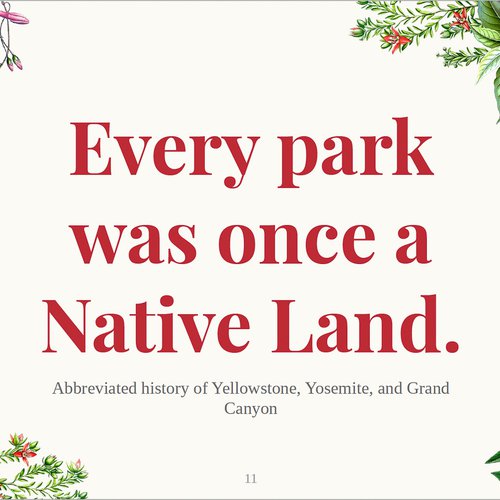

Reno Nevada, a student in Anno’s course, researched national parks in the U.S. and the tribes that were displaced by those parks. Nevada exposes settler occupation, saying, “Parks weren’t made to preserve the landscape, but to be a pleasuring ground for the people, a piece of preserved land which was free from humanity’s touch. Writers and environmentalists during the time of John Muir were convinced that people and nature are supposed to be separate.” This doesn’t bode well for the original people who view humans as an inseparable part of nature and who have always been stewards of the land.

Material culture

Arima’s course is called Hand to Mouth: Questioning Consumption. It teaches “how jewelry and food preparation craft our essential, emotional, and physical existence.” It investigates material and global relationships and their impacts on culture. “We spent time talking about Indigenous populations in the Bay Area and the U.S.,” says Arima. “It was eye-opening for non-Native students to discover that the original people are still here, and to learn about atrocities—like the enslavement of California people.”

On consumption, Arima says, “One of the things I have students do is write down everything they throw away, everything they bring inside, everything they recycle. It makes them hyper-aware of their use of materials. Since we’re a metals class, we also talk about where metals come from, about extraction, and about using suppliers that only use recycled metals.”

“With the food-related part of the class,” Arima says, “they’re researching a cultural recipe, then examining all the ingredients to see if there’s one that has a harmful or positive environmental impact. If it has a harmful impact then they find something that replaces that. It gives them a sense of being connected through culture and through their own personal belief system and gets them motivated to make some shifts.”

Students have skills

CCA students bring many skills and experiences into the classroom. “Students I work with are gifted at visualizing how social life and environmental systems are shaped by the boundaries and materials of cities,” Kim says. “They see segregation and a lack of access to resources, housing, and public space because it’s happening right in front of them. They reveal rich comparisons, like one that came up in my seminar between the Chinese government’s 70-year time limit on private ownership and the North American tendency to think of property as eternal.”

Kim says, in the Urban Imaginaries course, “the combination of students’ varied skills helps us build a bigger picture of the way social and environmental justice come together. In my studio last fall, one student was especially observant about everyday social interactions around tactile interfaces—like a bike pump—while another was super insightful about understanding urban policy around vacancy taxation, and another brought in a historic perspective of a site’s previous life as a wetland. Each scale informed the other, helping us understand how public access to social space and ownership works today, and how it could be reimagined in the future to make the city available to a much broader public.”

Who is the audience?

“When students talk about their audience,” Anno says, “I ask them to be specific and not homogenous. They always say ‘my audience is everyone.’ That’s like saying, ‘Everyone is free. Everyone is equal.’ It’s not at all helpful! Do they want to make work that is about the homeless for the homeless? Or do they want to make work for a museum-going audience? Sometimes students will define their audience as being like themselves. Sometimes they reach across an ocean.”

We learn how to define and speak to our audience over time. “One of the most important skills for students—and everyone—to learn,” says Kim, “is to reflect our unique perspectives while drawing out the knowledge and values of others. This is critical given how differently environmental burdens are distributed among diverse communities and the varied attitudes toward the environment that we each hold.”

Thinking about audience “forces us to think about the role of class, government, society, and business—the role that all those strata play,” says Anno. Fiss appreciates bilingual students, “working with activist movements in the past, that’s always been a blind spot, not just in terms of linguistically translating, but also culturally translating” between makers and audiences.

Powerful together

Creators have power within themselves and how they use that power is key. When there’s a fear of what’s next after graduation, they may say to themselves things like, “Once I graduate, I have to sell my brand. I have to brand myself,” Fiss says. “For juniors and seniors, they’re worried about the economy and their portfolio.” But in justice movements, it’s more about collectivity and collaboration. “Taking one’s self out of the center of who the work is for is a big step,” says Fiss. E-school students can learn to lift each other up amid chaos, build a foundation of community even while distancing, and grow to understand that they are unstoppable together and in collaboration with the Earth.