Sustaining change: A nature narrative in four parts

A growing community of Design students are leveraging their assignments and projects to express care and concern for the planet.

Prelude

Housed within the Design division at California College of the Arts is a small but growing community of students leveraging their course assignments and thesis projects to express a sense of care and concern for the health and well-being of the planet. They are supported by an expanding group of faculty experts teaching across various design programs. Together, students and faculty have been defining a more responsible design ethos—one that helps mitigate harm not just to the planet, but also to our very human existence. And, they’re doing so in really novel and interesting ways. Take, for example, the following student projects and consider how you too might want to bend your lens towards nature’s calling.

Part I: Terra Cards

Imagine that a design brief from the year 2050 has landed in your inbox. The client is anonymous. The goal is ambiguous. The problem is uncertain. The stakeholders are unclear. Yet, you’re intrigued. In fact, with an ounce of hope, you opt-in to design for a world in lockdown not because of a virus but because of an inability for humans to survive outdoors. It is a world consumed by pollution, severe weather, and a perennial stream of wildfire smoke. After an intense period through the speculative design process, you arrive at a “diegetic prototype,” an object from this distant, but perhaps not quite so distant, future.

Eryn Bathke, Terra Cards.

With a speculative eye toward what lies ahead, you explore a design solution to help your fellow future beings grapple with what you’ve surmised is a deep sense of “ecological grief.” Your first prototype is a deck of Terra Cards. Each card represents a particular plant to aid humans in a non-physical but spiritual connection to nature. You’re ready to test your prototype. However, you only have access to users in the present. You’re OK with this because these users will eventually meet their future selves in this 2050 scenario.

This is the nuanced, detailed, and thoughtful work of Eryn Bathke (MFA Design + MBA Design Strategy 2022). Bathke credits speculation as “one of the best things that has happened to my design practice” because in it, she “found this thing that could help tell this narrative” in ways that she hadn’t been able to in other mediums. For her part, Bathke wants us to know that “nature shouldn’t be treated as a siloed system that we elevate ourselves from because we aren’t just from nature—we are nature.” She adds that “once we realize this true interdependence and are able to view its value in new ways, we will grow with nature and not apart from it.”

Part II: Bedrock

Now consider the work of Ainsley Carter (BFA Interaction Design 2022), who deftly turns our attention to the present. For her part, Carter doesn’t want climate change “to feel like something far off into the future.” Bedrock—her ambitious and multi-layered project—is deeply personal. With an early interest in “activism and understanding current events,” Carter concedes that “climate change has always stood out as a controversial issue.” Embodying an almost intuitive insight into the needs, behaviors, and motivations of her present-day target audience, Carter was keenly aware that she would need to take a different approach, one that would find her sidestepping “buzzwords like climate change.”

Ainsley Carter, Bedrock.

Carter believes that “a lot of the designs that we see around climate change are preaching to the choir.” She further explains that these messages are typically “geared toward an audience that already has an understanding and acceptance.” Armed with a set of five personas and their accompanying journey maps, Carter chose instead to focus on a community that was more familiar to her, those whose lives revolve around “agriculture, livestock, hunting, and snow sports.”

Further inspired by lifestyle and reality TV networks like Discovery, Carter positioned her project Bedrock as the “only channel at the intersection of nature, lifestyle, and news.” Each of her series concepts is tied to a mascot that she says audiences can “invest in over time,” thereby building a more personal and lasting connection to climate change. According to Carter, the mascots are intended to help audiences circumvent their “initial reactions, judgements, and biases.” Bedrock’s other touchpoints include a website and an AR app. Carter hopes to find time to continue developing her Landon the Longhorn mascot.

Part III: Project X

Another student, Sarah Zaheer (BFA Interaction Design 2021), has been working on not one, but four special projects, each with a nod to sustainability. Zaheer was originally so moved after reading the book The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming, she still remembers her shock in thinking that “the planet may not be here.” Yet for Zaheer, the problems are very much in the present. Having grown up in India, she has seen “smoke and pollution affect people so badly that they either aren’t able to breathe properly or die from the smoke.”

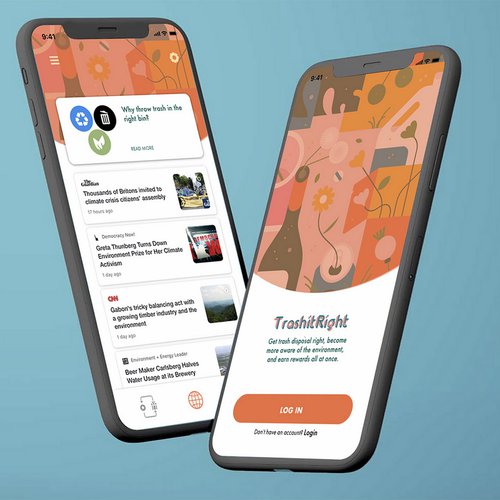

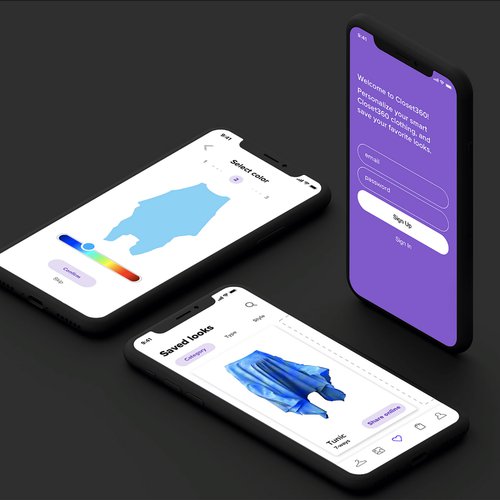

Zaheer is keen on leveraging her projects to bring a greater sense of awareness to these issues because she doesn’t believe that many people know or care enough. Consequently, she’s using every project opportunity to weave in a sustainability thread. Her project Redux is a concept for an e-commerce website that helps people buy sustainable products. Another project relies on gamification to incentivize proper trash disposal. Zaheer has even tackled the world of fast fashion, having prototyped a garment that gives one the freedom to wear it in multiple ways, thereby negating the need to “buy more clothes.” For her senior thesis, Zaheer designed a product that would help e-commerce shoppers track their carbon footprint. Now imagine having Zaheer on your team?

Zaheer wants designers to care more about sustainability because she knows that designers have the power to spread awareness through their designs. Probing even deeper, Zaheer says that she wants designers to “evoke empathy not just for fellow human beings but also for the environment in which they live,” imploring designers to “care more about everything around them.” While her projects center the present moment, Zaheer is a futurist in her own right. She wants future generations to live in a better and more sustainable environment.

Part IV: Tour De Trash

Anton Castro (BFA Interaction Design 2021) and Ryan Kilmer (BFA Interaction Design 2022), are taking on big trash. Working as a team in the Climate Design course with Adjunct Professor Marc O’Brien, the duo wanted to use their interaction design toolset to raise awareness and promote action on climate change. For his part, Castro viewed trash as the “unsung hero of climate change.” Kilmer, on the other hand, saw it as “out of sight, out of mind for most Americans.” Confronted by the scale of what they referred to as the trash crisis, the two set out to not just create a sense of awareness about the problem, but to also hone in on “actionable things that people could do after interacting with our design.”

Anton Castro and Ryan Kilmer, Tour De Trash.

The only given was that the experience needed to be fun. Somewhere throughout the creative process they also determined that they wanted to deliver a creative solution that could reach people at a broader level. To them, that meant weaving in what was popular, relevant, and familiar. Although the duo drew strategic inspiration from certain brands, they wanted to push the needle a bit further. Enter the concept Tour De Trash, described by the two as a “bike race similar to the Tour de France, but instead of racing around beautiful destinations, competitors race to and through America’s largest dumps.” Castro and Kilmer went even further, exploring a partnership with Peloton so that riders could “experience the scale of the trash at home.”

Overwhelmed by the unimaginable amount of trash that ends up sitting in landfills awaiting an end-of-life fate, the team zeroed in on impacts to the environment should waste reduction not be prioritized. Kilmer says that “letting it sit there to decompose emits ozone in the atmosphere.” He also made note of the “huge impact” that waste has on the “chemical makeup of the soil, water, and area where it is disposed.” He added that they also considered the impacts locally and globally and that this had a big influence on their solution. Ultimately, says Castro, it was about “focusing on the story as opposed to the data and big headlines.” Reflecting on what they want to get across to designers, Castro says, “If you want to clean up the world, you have to get your hands dirty.” Building on this, Kilmer adds, “Don’t be afraid to tackle big issues because they’re political or because they’re social justice related.”

Epilogue

In these projects we find glimmers of a hopeful, playful, and energetic optimism that dances on the borders of a world that is so obviously in the midst of massive change. What sets these students apart is their direct willingness to explore the infinite possibilities of design. These are just some of the qualities of original thinkers and of true design innovators. These designers exist across the Design division and the accolades, though not the intent, have indeed followed. Tony Zhou and Dhaval Thakkar, both Industrial Design students taught by Ian Coats MacColl, recently received the Global Footwear Awards’ Silver honor for designing “adjustable shoes that grow with kids.” How might we help sustain this change?

—Sasha Charlemagne

May 11, 2021