Listening for the future

CCA Design Futures Lab, Imperial College London, and LADdesign join forces on summer design sprints that explore the future of music experience through design.

Learning from the future

The Future of Music is an ongoing collaboration of CCA's Design Futures Lab with Global Innovation Design program in London + Lawrence Azerrad of LAD Design in Los Angeles.

Across CCA’s Design division we are diving into the generative space of the future—where designers present future scenarios to ask questions about what we might be overlooking in the present. Helen Maria Nugent, dean of Design, explains that this work, often called speculative design or future design, creates new frontiers in creative practice. “It helps us to think expansively and elevate design as a tool for critical thinking and creating alternative narratives, which can transform how we imagine our relationship to this world.”

Design speculation can approach contemporary problems that are complex and challenging, such as resource distribution, surveillance, dehumanized algorithmic decision making, and ecological collapse. The outcomes are usually a fictional artifact or storytelling device, not intended to solve a problem but to provoke conversation. As such, they require a suspension of disbelief and the kind of willing engagement that we need when reading an allegory. The designer’s goal is less about offering a solution and more about provoking conversation. “Oh, I hadn’t thought of it that way,” or, “Is this a future we want?” are desired responses.

Futures thinking is a valuable framework and method in education because it offers fresh pathways and centers on the future, a destination that all should have access to and responsibility for. Here, we share some of the ways future framing is integrating with design education at CCA, and invite our readers into the speculative discourse taking shape in our community.

Delimiting music experience

Although speculative design can take the form of dystopian visions, there are also many design futurists who want to see the future as an expansively positive set of options. Lawrence Azerrad’s summer design sprint program, Designing the Future of Music (DTFOM), is more along these lines. Here, student-made works offer equitable, joyful experiences through new possibilities, transforming technologies that we can only see a glimmer of right now into tools of agency for both listeners and musicians. “Designing the Future of Music asks us to use speculative design to explore how we can connect more deeply to music and everything that music holds,” says Azerrad. “It’s more than album artwork, its [purpose is] to crack open new ways we can connect to understandings of each other and our cultures, stories, and histories, perhaps using media not even invented.”

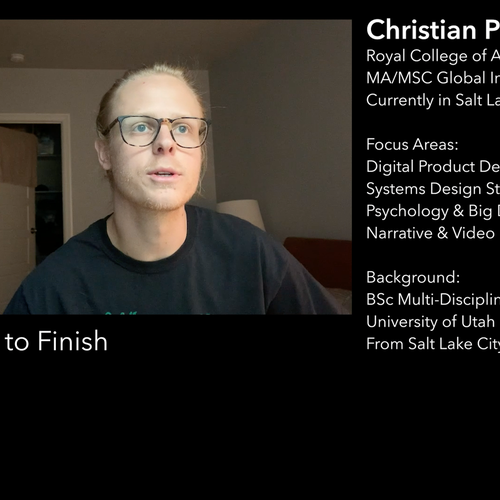

DTFOM is a collaboration with CCA’s Design Futures Lab and Global Innovation Design (GID), a joint program between the Royal College of Art (RCA) and the Dyson School of Design Engineering at Imperial College London. Nugent explains that the collaboration exemplifies the ethos of CCA’s Futures Lab by “demonstrating how interdisciplinary collaboration, global partnership, and creative research leads to ideas that can transform our world for the better.” Now in its second year, DTFOM offers a space to explore and iterate expansively on the role of design in music, how it is made, distributed, and experienced. Students benefit from the convergence of their experience with speculative methods and access to deep industry insight. The program begins with two days of presentations from industry professionals and artists who introduce their own work as well as the broader concerns of the industry. Students then break into inter-college teams and dive into a design sprint that proposes a vision of how our experience of music could feel and behave in the near future.

Narrating possibilities

Sara Dean, chair of the MFA Design program and founder of the Design Futures Lab, has relished this collaboration. “Music is such a wonderful way into larger questions. We are able to speculate on solutions to very specific technological, economic, and experiential problems facing the industry as well as have larger conversations about the implication of these issues across many industries,” she says. “We started the program at an unprecedented moment [in the summer of 2020], on the cusp of COVID-19, when live music and social connection were challenged and being rethought. The program had the opportunity to ask questions about social connection, collective experience, artist compensation, culture, inclusion, and distributed technology from this vantage point.”

The students in the 2020 sprint proposed digital projections for interacting with street performers, links between taste buds and music, and gamified karaoke-like group activities. They saw music as a thread that could enter social and private spaces, capitalizing on both familiar and novel technologies to deepen, diversify, awaken, and critique current models of musical experiences. Projects were sent back and forth between CCA and RCA as ideas gained momentum and sparked off one another. Final proposals were exhibited at the 2020 San Francisco Design Week virtual festival, as well as in the Museum of Design Atlanta (MODA) exhibition The Future Happened, which opened in February 2021. Azerrad explains that the exhibit is organized by six tracks—Healing, Power, Community, Technology, Timeless, and Atlanta—with many artists and works presented in multiple tracks to show connections that are deeper than traditional genre labels. As the MODA exhibit opened, Nugent and Azerrad came together to talk with artists Rochelle Gribble and Nep Sidhu from the 2020 program, and to ignite the 2021 teams on their journey.

In the 2021 sprints, three MFA Design candidates—Jody Hurt (DMBA 2022), Keyu Mao (MFA Design 2021), and Chancie Zheng (MFA Design 2021)—joined students from GID, and were led by Lawrence Azerrad, Leila Sheldrick from GID, and CCA Professor Jiwon Jun. Areas suggested for research were collectivity and connectivity, remuneration, artist voice, activism, tangibility, value, healing, love, and time. These projects will join the MODA exhibition and will be shared and archived on CCA’s Design Futures Lab website along with the 2020 projects. Jun was delighted by the students’ work as they overcame the challenges of timezone-crossing meetups. “I really enjoyed that it was not only about making something new or convenient, it was about taking a critical perspective on how we consume and listen to music, and proposing ideas of what could be an alternative in the near future,” she says. Jun also notes the benefit of having students from the two schools, with a wide range of training and experience, each bringing their skills to the process. “This makes sense as an approach to design. Design doesn’t exist as a single thing, it’s interconnected with so many different things—social context, technologies, aesthetics.”

In Trace, artists geo-tag their recordings or live performances to locations, so that as listeners move physically they experience a spatial soundtrack. This is meant to encourage physical movement as well as provide new access points without using advertising and other traditional attention-grabbing mechanisms. InnerSleeve proposes the use of NFT and blockchain technologies to trace music files as they change hands, enabling artists to map and clarify ownership and royalties for more fair remuneration and to shrink the capital gap between production and consumption. Spill the Tea is a complex piece using public installation, custom-printed tea bags, and layered vocal tracks to amplify LGBTQIA voices, merge action and listening, and raise funds for community support. Mao, who was on the Spill the Tea team, describes their realization that “music experience is no longer limited to the sharing of feelings or emotions. It can be a carrier of thoughts and activism that everyone can participate in, interact with, and evaluate.” Secret Sauce combines the physical act of passing music with the digital sharing of samples and mixes. Users add QR codes to a physical book to share their own music-making recipes. All of these proposals are warm-hearted, and could, like many future visions, be seen as too optimistic. But we have to dream our way beyond the matrix of the present.

Weaving into critical pedagogy

This kind of leapfrogging over technical barriers is part of how speculative design can liberate our imagination. Dean explains that “the format of the work is a reflection of the Design Futures Lab's goals, connecting industry and academia, studying pressing issues, and exploring possible future alternatives for more inclusive, resilient, and thoughtful solutions.”

The Design Futures Lab and DTFOM are part of a longer thread weaving through the entire college, from undergraduate Foundations in Critical Studies courses like Critical Making taught by Saraleah Fordyce that introduces speculative tools, to entire courses dedicated to futures literacy such as Design Research for Speculation taught by Nugent, and Theatre of the Future taught by Associate Professor Kristian Simsarian. MFA Design Associate Professor Scott Minneman regularly brings ideas from his work as a research affiliate at the Institute for the Future into the classroom.

By the end of their time at CCA, many students produce highly resolved visions of futures that exceed what feels possible, raising the wicked questions that cannot be addressed with design’s traditional problem-solving methods alone, like Eryn Bathke’s (MFA Design 2021, DMBA 2022) thesis addressing eco-grief or Yuan Jiang’s (MFA Design 2020) visions of a future where humans and animals engage in symbiotic and empathetic practices to share a resource-desperate planet.

When the problem lies not only in what we do, but more deeply in how we think, we need tactics that challenge and shift those deeper pathways of belief. Thought-challenging and conversation-sparking are sweet spots for discursive and speculative work. Over the coming semesters we’ll continue to share how this emerging field of practice weaves into our programs and interrogates our assumptions as designers and citizens, pushing us to embrace our role in a fast approaching future.

—Saraleah Fordyce

August 25, 2021