Design pedagogy for collective work

Three pedagogical designs at CCA that transcend individual learning.

As we build programs, degrees, and education, we are really investing in individuals. We want to see students thrive, to open doors for them to grow beyond what we can imagine. Their not-yet-made dreams are the stuff of our collective future. But they won’t build it alone. We need to cultivate, sponsor, and support a generation of designers who are facile listeners and collaborators, who do things with others that transcend what they could do on their own.

Yet so many education models assess and reward individual work and promote a competitive learning environment. In media scholar John Fiske’s 1992 essay “Culture, Ideology, Interpellation,” he describes the ideological apparatus as including education, with its endorsement of patriarchy, individualism, and competition. There is a call, from writers like education theorist Asao Inoue and others, to question how we build these value systems in our classrooms, suggesting that we can make courses where students rise together rather than separately.

With that in mind, let’s look at three pedagogical designs at CCA that center and teach collective work: a collaborative music timeline assignment by Juan Carlos Rodriguez Rivera, taught in his course Designing Our Way Out; a graphic design studio, TBD*, taught by Eric Heiman and devoted entirely to student teams working with local organizations; and a workshop between students from CCA’s MBA in Design Strategy program and the University of Tokyo i.school.

Tracing geo-political threads in Designing Our Way Out

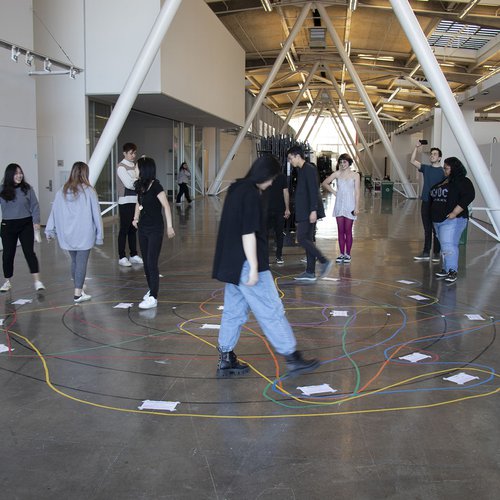

Assistant Professor Juan Carlos Rodriguez Rivera teaches a course in MFA Design called Designing Our Way Out. Graduate students focused on graphic, interaction, and industrial design come together to study “the role of design in the creation of culture and in practices of liberation.” A key assignment that Rodriguez Rivera has been developing over years in his course Decolonization & Design is the “Non-Linear Incomplete Music Timeline,” for which the entire class researches the influences and confluences of music movements. This “allows students to make novel global connections using music and time as the threads,” Rodriguez Rivera says, and to ask questions like, “How do we talk respectfully and responsibly about someone else’s culture and music?” When students learn about music they also learn about race, gender, and class, Rodriguez Rivera explains. An important theme both culturally and pedagogically is reciprocity—music does not funnel from one place to another, it weaves between people and places, evolving and transmitting new meanings as it flows.

They start by talking about Puerto Rico because it is where Rodriguez Rivera is from and is a way to “discuss colonization and Diaspora,” he says. “Music is a way to trace those geo-political threads.” Once the research starts to take form, student teams work to experientialize their findings. For Rodriguez Rivera this is a joyful experience of collective knowledge building. “We create new thinking that is beyond chronological,” he says. “Because it’s music, it’s so fun and everyone enjoys it. I love that I am just another designer at the long table. I get excited when they are creating next to me.”

Learning Listening in TBD*

Associate Professor Eric Heiman teaches a BFA Graphic Design course called TBD* (to be determined, to be dedicated, to be diligent, to be designed), an in-house student-run design studio where teams are paired with small local nonprofits and civic organizations that need design support. Over the course of an intensive semester of collaboration, real and usable products are generated and launched.

It’s a radically practical model that Heiman says has changed the way he thinks about “who we design for, and how we do it.” TBD* evolved out of a program that Heiman was involved in as a CCA student himself in 1995, called Sputnik, which helped students practice real-world design assignments under the guidance of Professor Bob Aufuldish. TBD* is meant to “expand the notion of what design is, what it does,” Heiman says, “to expand the benchmarks of what good design looks like.”

Students have to apply to take the popular course, it runs in both fall and spring semesters so more students have a chance to participate. Partnerships are arranged over the summer, when Heiman and Tracy Tanner from the CCA Center for Art and Public Life put out calls for projects, usually setting up four per semester. There is a strong pedagogical emphasis on learning the ethos of the partner organization, and student teams meet with the external partner for 30 minutes each week. Students have to both assert what they think should be made, and act from a place of humility and listening. At the end of the semester, Heiman is delighted when partners say things like, “You really listened to us. This is really us,” he says.

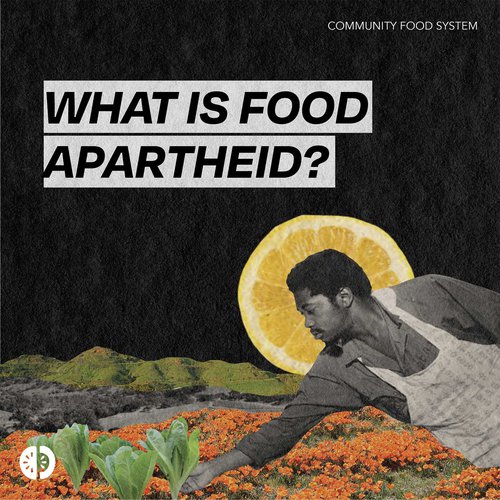

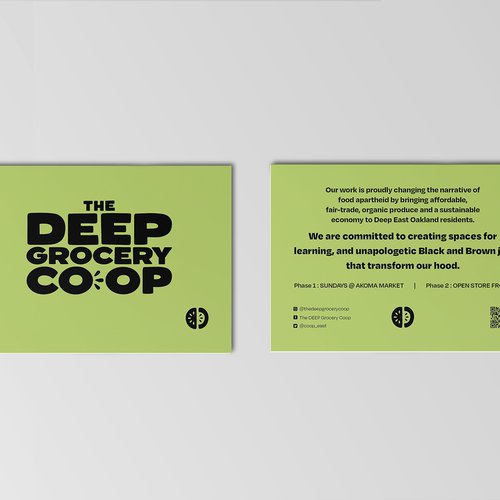

Kajri Popat (BFA Graphic Design 2021) took the course in 2020 and worked on branding systems for Clown Corps and The San Francisco Schools’ Citizen Girl* summer camp. She says the course taught her that “listening to feedback and comprehending feedback are two very different things. Hearing how happy they were was so gratifying. Now, seeing my work on their websites gives me so much pride.” Another student, Amanda Lee (BFA Graphic Design 2021), worked with The DEEP, a worker owned grocery co-op in East Oakland addressing food apartheid and food deserts. “It was a great collaboration working with Yolanda [Romo] making infographics, and I hope to bring that energy and activism into my work moving forward,” Lee says. “It taught me so much about our food system and the inequalities in food access.”

If you peruse the projects on the TBD* site (highly recommended), you’ll notice the gorgeous, professionally presented collection of work, a deep gallery in a range of styles, but with a common aim. This is about partnership, it’s about using our collective voices to shine a light on work we believe in. “One aim is to recognize that we’re a unit, each with individual responsibilities, but a unit,” Heiman says.

Reciprocity by Design

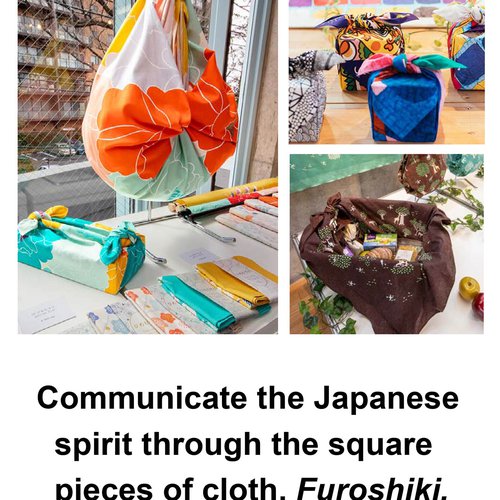

In the spring of 2021, CCA’s DMBA program and students from the i.school at the University of Tokyo collaborated in a workshop to produce future scenarios for a select group of Japanese legacy businesses. The workshop was initiated by Barry Katz, who teaches in programs across CCA and is a fellow at the i.school, and run by DMBA Chair Sara Fenske Bahat and i.school Director Hideyuki Horii.

The Bay Area has tended to valorize novel, fast-moving ideas. Startups, earthquakes, counter culture. We specialize in the reimagining. Japan is home to at least 140 businesses that are more than 500 years old, with more than a dozen operating since the first millennium. The i.school has developed a workshop model to share their unique approach and brought a selection of Japanese family run, high-craft legacy businesses interested in new design insights and applications for the contemporary market, like the Hoshinoya hotel chain and Horikin, a metallic powder purveyor established in 1711.

Teams of students from both schools iterated and pitched to a panel of judges future scenarios ranging from VR soundscapes for the hotel to crackers made from food waste in urban centers. “The goal was to explore what one side of the world could learn from one another, what we could question about our assumptions in search of better outcomes on both sides,” says Bahat. DMBA student Camila Reyes Camacho (MBA Design Strategy 2021) echoes that, for her, the value was in practicing exchange, in asking questions. “The more you understand [about your collaborator’s perspective], the better facilitator you are,” she says.

Students from across the Design MBA program met three hours every day for four days and worked on ideas between sessions, ending in presentations tailored to the participating businesses. Bahat says the businesses shared many of the same characteristics. “They look out for family and community over profit, with an obsession on craft,” she says, adding that both give a window into another kind of business model, a different approach to capitalism. The workshop “was hugely successful on both sides of the Pacific,” Katz says, and it has him reflecting on the fertile ground opened up by the tools of remote interface. His partnerships in Italy, Israel, and Colombia hold promise and inform his interest in cross pollination as a generative practice. The i.school brought a structure they have developed to the interaction, and Bahat is interested in developing CCA’s own, fueled by the research and practice in the DMBA program. Offering skills, learning from others, applying theory—this model positions our students to recognize and benefit from exchange.

Conscious choices

Fiske, in his writing on ideology, emphasizes that the reinforcement of individualistic values happens without trying, but resistance is conscious and intentional. In our many quick pivots of this era, we must turn and listen to others. Through these courses, assignments, and interactions, students and faculty are working to build, teach, and manifest the value of reciprocity. This disposition of learning from and with one another is key as we face the future together.

—Saraleah Fordyce

May 11, 2021