Life before, during, and after CCA with Individualized Studies alum Galen Boone

At 25, after receiving her first degree in archeology, Galen Boone (BFA Individualized Studies 2019) realized she missed making art, so she applied and got accepted to one of the best jewelry and metal arts programs in the country.

Tell us a bit about yourself and your work

I’ve been, among other things, an almost-archaeologist, a butcher shop apprentice, and a bad vegetarian. Today, I’m building a life post-CCA as an artist and jeweler.

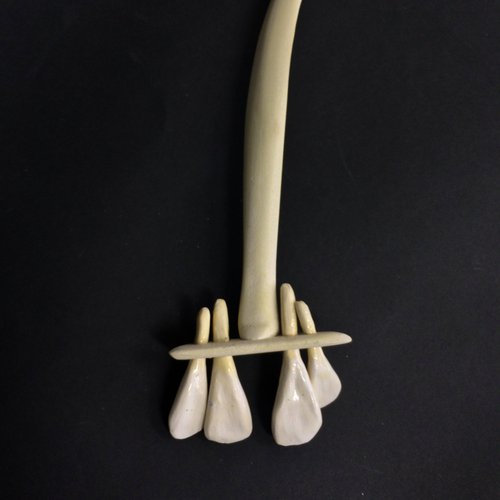

As for my work, I make lovingly perverse sculptures and wearables for queers, freaks, and outsiders. In my current project, I counter the myth of binary gender by offering my own panoply of sybaritic gods, adorning androgynes in strange jewels—anatomical armor, metal pubic hair, enameled nipples spilling drops of bone “milk”—and posing them in an alternate jungle of Eden.

“In a moment in which LGBTQ rights are eroding, I want to re-deify the people and bodies that violate the binary.”

BFA Individualized Studies 2019

Galen Boone, headshot, 2018. Photo by Alexander Wong.

Queerness is a central theme in your work. What are some of the main messages that you hope to convey?

I’m interested in moments of binary collapse, especially in and around the body.

To put it bluntly, I’m a genderqueer dyke making loving propaganda to challenge the denigration of queer people and our erasure from histories.

If the only true or natural genders were “woman” and “man,” we wouldn’t need to police gendered expression with shame and violence, and we wouldn’t be able to see gender(s) shift over time and across cultures. We’ve been told that gender variance and same-sex attraction are perverse, or aren’t real, or are less valid than heteronormativity. But gender variance is all over the archaeological record, like the Middle Kingdom of Egypt’s third gender, sekhet, or the kur.gar.ra (“man-woman”), the sacred concubines to the gods in ancient Mesopotamia.

Throughout our history, queer people have been linked to the divine, and in a moment in which LGBTQ rights are eroding, I want to re-deify the people and bodies that violate the binary. The Supreme Court is likely to remove protections for LGBTQ people from the Civil Rights Act in the next year, and I figure we can use all the images of queer gods we can get.

Tell us a bit about your experience as an Individualized Studies major. Why did you go this route?

In my Core Studio courses, we were assigned projects in different media, so I ended up cutting antique medical books for collage, sculpting barbarian utensils out of clay and wood, and filming a short about a murderous roller skater. I discovered that while jewelry got me in the door to art school (and it’s a deep and true love), my sweet spot is really the disquiet between attraction and disgust. I hunt for that electricity in different places—like in three-legged tables with furry bellies!

The Individualized Studies program is a cohort of driven students whose work doesn’t fit in a single major, and [associate professor] Christina La Sala and other faculty helped me advocate for myself and the projects I could see in my head. In my first few semesters, I remember feeling like I had been gestating this luxe-barbaric aesthetic for years and at CCA I could finally start giving birth. As an older student, I knew the direction I wanted to go in; I just needed the agency to build my curriculum to get me there. As an "Indi" major, I got to sew velvet palm fronds, and perform as a cannibalistic cave kid, and dive deep into metalworking, and build half-eaten ceramic cadaver parts that double as serving trays.

What courses had the biggest impact on your personal growth and practice?

Even though I didn’t need to as an “Indi” major, I took every jewelry/metals class I could. The learning curve for metalworking is humbling, often agonizing, and then so satisfying. And I sincerely love my professors: Deb Lozier taught me that metalworking is a conversation between an idea and what metal actually wants to do; Marilyn da Silva saw through my fear and asked me to jump into the deep end of the pool (hello, Bank Project); David Cole keeps showing me that where there’s a will, there’s a way; and Curtis Arima understood where my work was coming from and would gently, lovingly steer me back on track.

I took several classes with ceramics professor Kari Marboe, who is big on performance and weirdness; she hurled me outside of my comfort zone.

Individualized Critique helped me hone my thesis project, and associate professor Angela Hennessy’s course Over My Dead Body changed my life.

What have you been doing since graduation?

One of the most important experiences I’ve had post-graduation is spending two months this spring at Penland School of Crafts. I took art jeweler/total cowboy Lola Brooks’ metals concentration and found a friend and mentor. Lola’s a study in extremes: Her jewelry is irreverent and almost obscenely girly, and the underlying metalwork is fastidious and supremely skilled.

I spent this summer traveling through Europe to places like Copenhagen, Venice, Berlin, and Athens as a part of a research trip to study ancient jewelry and metalworking techniques. I ogled so much Greek gold, Roman bronzes, and Byzantine enamel I still have glitter fatigue. One of my favorite days was spent sketching in the Royal Armoury of Turin. My brain nearly exploded with ideas for more anatomical armor!

I’m back in the bay for September, and then I’m closing out the year at a silversmithing school in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. I saw thousands of pieces of jewelry on my trip, and I’m eager to have serious studio time to flesh out those inspirations and learn from a historic metalworking tradition.

What’s next for you?

I’m not sure what the new year will bring, except that I was named the Joshua Tree National Park artist in residence for spring 2020 (when I heard the news, I ran outside and squealed a whole bunch). I figured they’d pass on an artist who makes metal pubic hair, so being chosen feels surreal and wonderful.

I pitched the Joshua Tree National Park committee a parure, or matching jewelry set, to transform the body and break down the false separation of humanity from nature.

There’s a growing water crisis in the western United States, and it’s already affecting the ecosystem in the national park and killing younger generations of Joshua trees. Scientists predict that the species' population will be down by half in the next century. As a native Californian, I know first-hand the effects of drought and wildfires, and the pleasures of long showers, car ownership, and plane travel (among other ecologically irresponsible First World luxuries). Humans are in a collective state of cognitive dissonance around climate change and personal comfort, so how can art make this global emergency personal?

I figure one way is to bring it on to the body.

I’m imagining hammered and forged forms in a tight language of materials and colors—copper and bronzes alloyed by hand, shot through with watery silver or bursts of dusty green-blue patina. I’ll return to the stark beauty of the desert to shoot the pieces on the body, framed in a narrative around water scarcity, femininity, and indigeneity.

Pursue your creative practice within a supportive community